On December 18, 1984, I turned 24 years old, and on that same date, with the exhibition Ouverture, curated by then-director Rudi Fuchs (the first foreign director of an Italian institution), the doors of Italy’s first museum dedicated to Contemporary Art opened in the Castle of Rivoli, on the outskirts of Turin in Piedmont.

The exhibition included works by artists representing conceptual art, minimalism, Land Art, Arte Povera, and the Transavanguardia. It was conceived as an ideal model for a permanent collection which, today, 40 years later, boasts more than 800 works.

In a recent interview, the then-director said: “It’s incredible, but they accepted all my proposals. Giovanni Ferrero (Councillor for Culture of the Piedmont Region at the time) and Alberto Vanelli (his chief of staff) had a quite admirable inclination towards madness.”

Thanks to that “inclination towards madness,” it was possible to carry out a project that, perhaps more for foreigners than for Italians, still represents a cutting-edge concept in exhibition-making.

The Castle of Rivoli was one of the Savoy residences in Piedmont. The unfinished building, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, consists of two structures: the castle itself, which we see today in its 18th-century form, and the opposite Manica Lunga (Long Wing), built in the 17th century and conceived as the picture gallery of Duke Carlo Emanuele I.

Between the two buildings lies the atrium, essentially an open-air space, at the center of which stand columns and pillars belonging to the grand redevelopment project by the Messina-born architect Filippo Juvarra (whom we’ve already encountered at the Venaria Reale), left unfinished due to a lack of funds.

Once owned by the Bishops of Turin, the property became part of the Savoy domains in 1247 and followed the fortunes of the dynasty until 1883, when it was sold for 100,000 lire to the City of Rivoli.

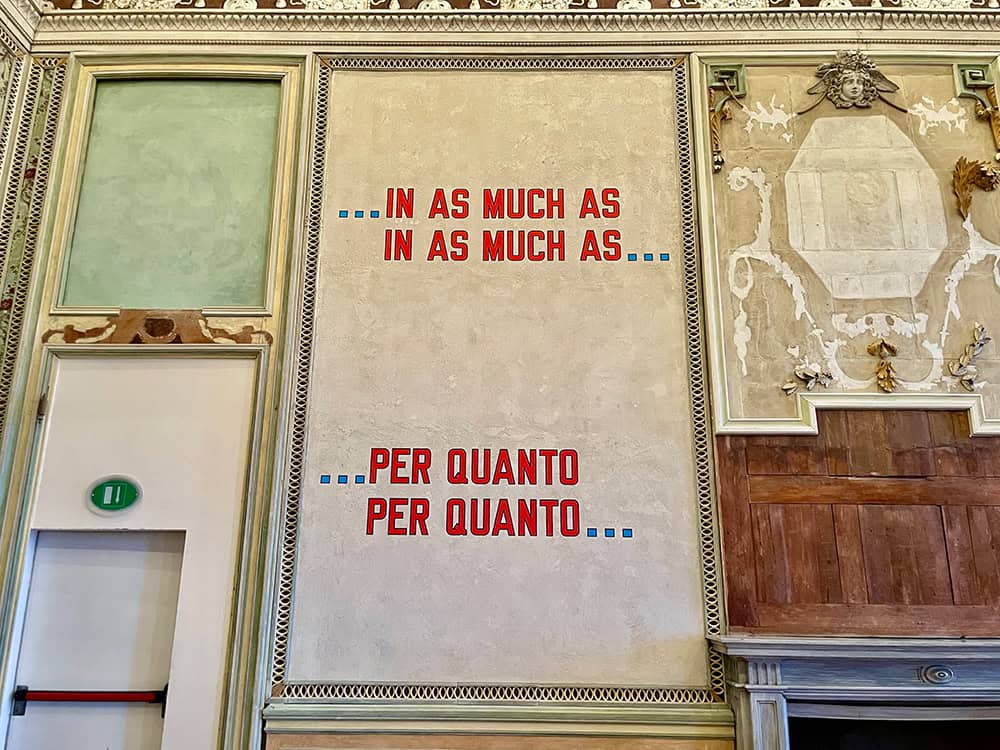

Over the centuries, the construction went through many vicissitudes, layers of history, and multiple affronts (in the 1960s it nearly became a casino). But thanks to the vision of a young architect, Andrea Bruno, between 1979 and 1984 a small architectural miracle was achieved, introducing rather innovative solutions such as the elevator, the large suspended staircase, the walkway over the late 18th-century ribbed vault, and the panoramic projection on the third floor, where modern materials like glass and steel are set within the austere walls of what was originally a medieval fortress.

Bold but effective solutions that blended perfectly with the building’s ultimate purpose—to host and engage in dialogue with works of contemporary art.

In those years, the Marquis and collector Giuseppe Panza di Biumo was looking for a home for his magnificent collection, which included works by Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra, Dan Flavin, Robert Morris, Donald Judd, Richard Long, and Carl Andre. At first, the castle seemed the ideal place to house them, but the Piedmont Region declined, so as not to betray the true mission of the Castle of Rivoli, which did not intend to become a conventional museum but rather a place for research and experimentation. (We will certainly devote an article to the venue later chosen by the Marquis to house his precious collection—Villa Panza di Biumo near Varese.)

Last December, therefore, the Rivoli Museum celebrated its 40th anniversary with various initiatives and an exhibition titled Ouverture 2024, precisely to recall the name of the show with which it was inaugurated back in 1984.

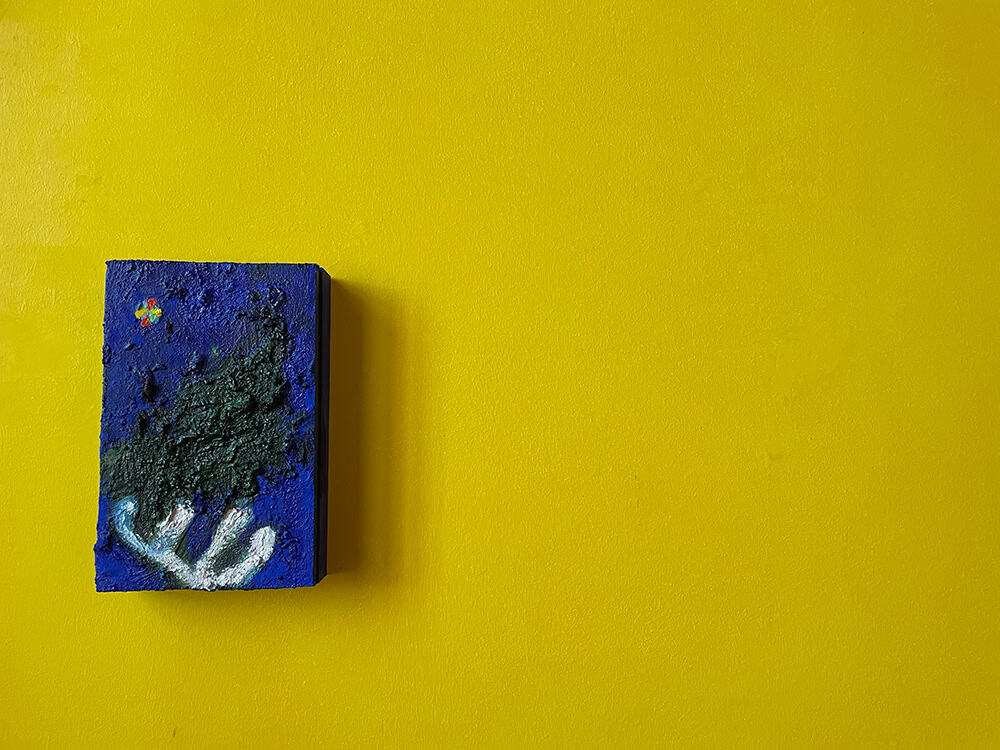

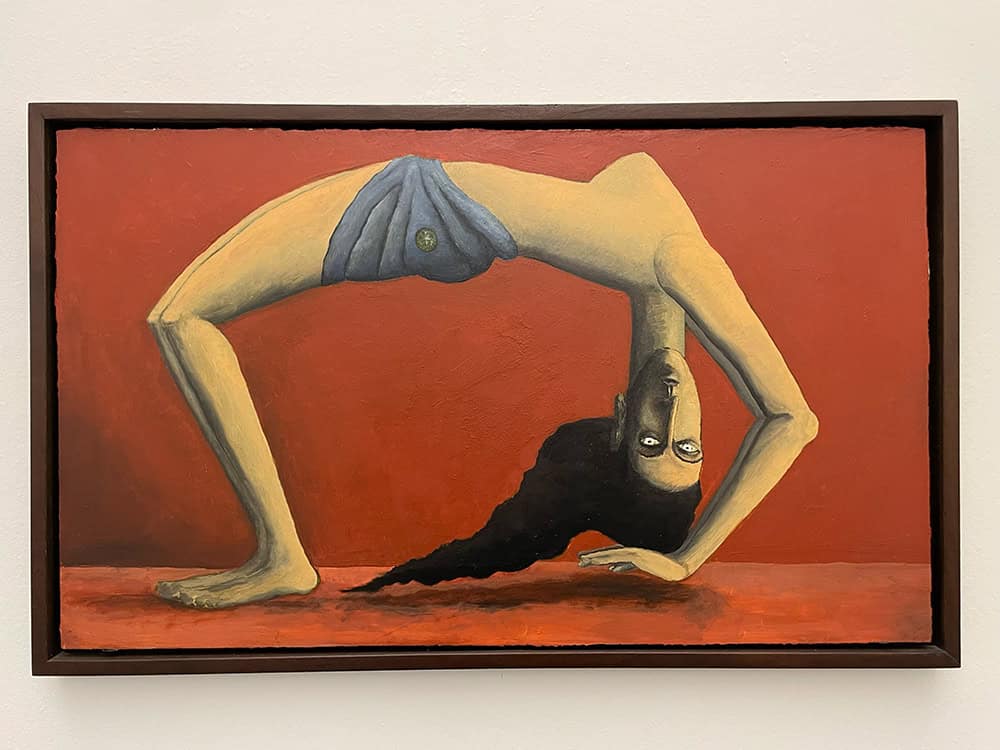

Visiting the castle collection feels both improbable and perfectly natural, as if the old structure walls were just waiting for these modern provocateurs to arrive and stir up its silence. The permanent collection here is not just a gathering of “important works” – though it certainly is that – but a living dialogue between the past and the present, between beauty and the discomfort of truth.

You turn a corner and suddenly there she is – Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Venere degli stracci. At first, your eye rests on the serene marble goddess, but then you’re pulled into the chaos of discarded rags at her feet, an unruly wave of color and texture. It’s beautiful and tragic at once, an allegory of our contradictions: the eternal and the disposable, the high ideals and the messy reality we live in. A few steps away, Maurizio Cattelan breaks the spell with his trademark mischief and sting. His Novecento – an embalmed horse hanging limply from the ceiling – leaves you with a tight knot in your chest, while Charlie Don’t Surf shocks with the image of a schoolchild pierced by pencils. These are works that don’t politely ask for your attention; they grab it, twist it, and make you leave with questions you can’t easily answer.

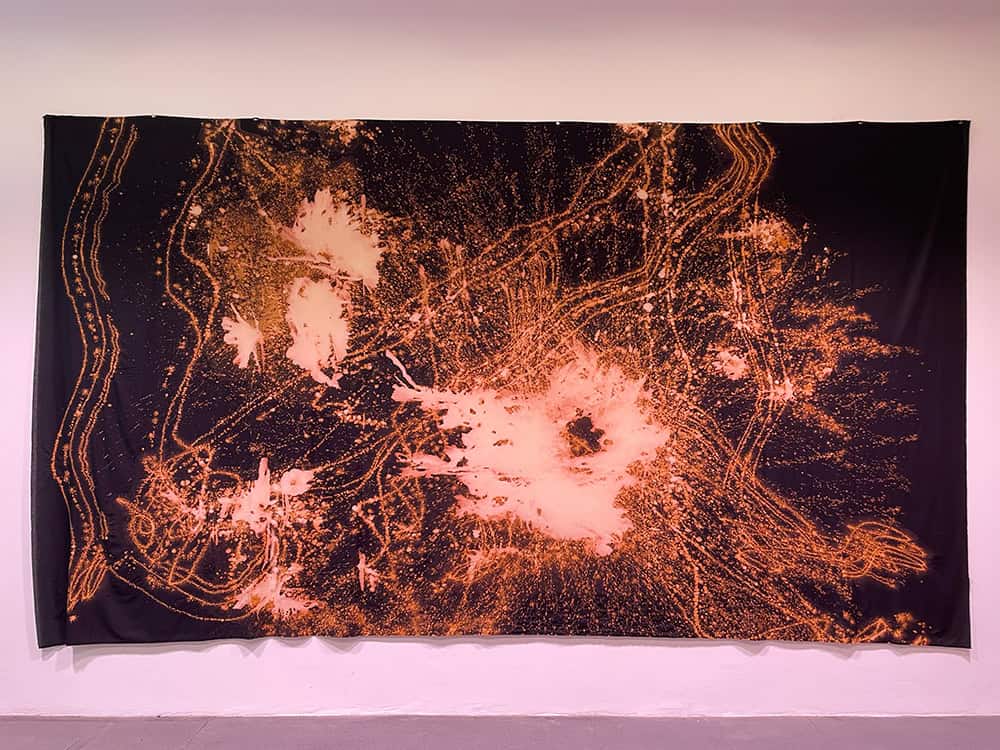

The Arte Povera and Transavanguardia masters are here too, their works as much a part of Italy’s cultural DNA as the frescoes of Florence or the mosaics of Ravenna. There’s Mario Merz with his igloos, a nomadic architecture of glass, stone, and memory. Alighiero Boetti’s playful intellect fills the room with works that are both cerebral puzzles and visual poetry. Marisa Merz, the quiet poet of the movement, offers delicate sculptures that seem to hum with an inner light. Giulio Paolini and Francesco Clemente weave together fragments of classical thought, literature, and dreamlike imagery, reminding you that Italian art has never been afraid to mix the sacred and the experimental.

International voices echo here as well: Joseph Kosuth’s conceptual rigour, Daniel Buren’s rhythmic geometries, Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller’s immersive soundscapes that transport you beyond the castle walls. And then, there are the newer acquisitions – like Aki Inomata’s ethereal wooden sculptures Yuzu I and Genie I, which explore the tender interplay between nature and technology. It’s reassuring to see that this is a collection still in motion, still curious about what’s next.

Walking through these rooms, you don’t feel like you’re simply visiting a museum. You feel as though the castle itself has become a stage where centuries of artistic thought meet, clash, and embrace. And as you step back into the daylight of Rivoli’s hilltop streets, the conversations you’ve overheard inside – between marble and rags, between horses and igloos, between past and future – linger with you, refusing to let go.

So, if you decide to visit Turin, don’t miss the chance to extend your stay in the city to enjoy a day in this paradise of contemporary art.

What I can wish for you is to see the Castle of Rivoli towards evening, when its slightly dreamlike walls stand out against the deep blue sky, so you can better appreciate its unusual shapes, its scars and their healing, the skewed space it occupies in the air, and wander among the severity of its tall walls and its unfinished voids. On the outside it is one thing, and on the inside quite another—its interior full of treasures that it contains with perfect ease.

You will leave the visit content—content that in the human world there are those who devote themselves to art, who make a profession of this love, and that someone can transform a castle ravaged by time and man into a chest that is both stern and gentle at the same time.

I am certain—you will love it.

Betti

How to get there:

The collection can be viewed here: https://artsandculture.google.com/partner/castello-di-rivoli-museo-d-arte-contemporanea