Who among you has not been part of the large group that enjoyed reading Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose (over 50,000,000 copies sold worldwide) and/or delighted in the ineffable Sean Connery as the lead in the 1986 film adaptation, will probably visit the place we are talking about in this article with less curiosity.

I mention the novel because the Sacra di San Michele in the Susa Valley, practically a symbol of the Piedmont region, was the inspiration for the story set in the Middle Ages and centered on the investigative adventures of the learned English friar William of Baskerville.

In fact, the film was shot partly at Cinecittà Studios in Rome (for the exterior scenes) and at the Eberbach Abbey in Germany (for the interiors), but Eco had long been struck by this place, which he had known since childhood, when he spent holidays at his uncle’s house not far from the abbey. He referenced it while imagining the dark, severe, and majestic atmosphere of the story.

When he sold the rights for the film, he would have liked the abbey itself to be used as the location, but the producer quickly convinced him that it would be cheaper to rebuild a medieval abbey from scratch than to film on top of a rocky mountain.

I had wanted to visit the Sacra for some time, intrigued both by what I’ve just told you and by another fascinating detail (even if, according to atheists and agnostics, potentially completely coincidental: with so many churches dedicated to prominent Catholic VIP saints,, it isn’t hard to align seven of them in a row).

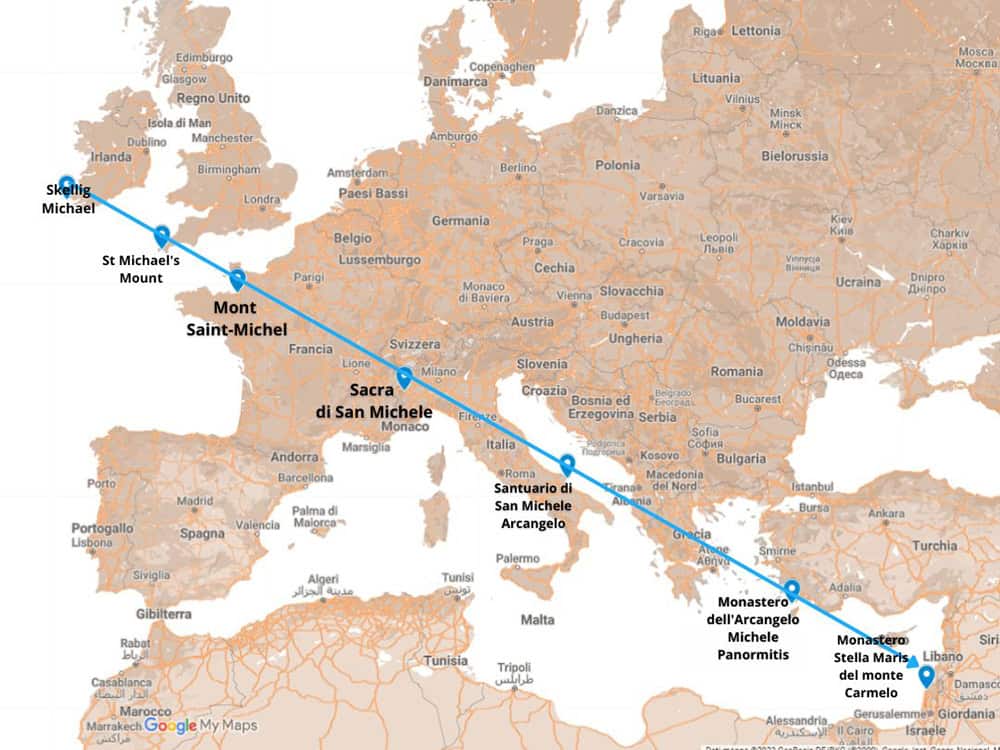

According to believers, the Sacra di San Michele lies on an imaginary 2,000 km line stretching from Skellig Michael in Ireland to the monastery on Mount Carmel in Haifa, northern Galilee, built in Byzantine times.

Along the way, it passes through five other major Christian sites: St Michael’s Mount in Cornwall, Mont Saint-Michel in Normandy, the Sacra di San Michele in Piedmont, Monte Sant’Angelo in Gargano (Puglia), and the Monastery of Archangel Michael Panormitis on the Greek island of Symi, in the Dodecanese.

These sites form what is known as the “sacred line of Saint Michael,” said to be characterized by restorative energy perceptible in each of the seven basilicas/monasteries. Legend has it that the straight line connecting them was traced by the sword of the warrior archangel during a furious battle with the Devil, whom he sent straight to hell.

We are almost a thousand meters above sea level, so the view should have been spectacular, but Nazim and I arrived on a day of low clouds; the Sacra was wrapped in a milky shroud. (Fortunately, our daughter visited some time later and provided us with photos of the panorama.) Still, apart from the frustration of missing out on the breathtaking view, we found ourselves in exactly what we imagine to be a medieval atmosphere: little light, penetrating dampness, and hostile weather.

There are several ways to reach the top: via hiking trails like the Sentiero dei Principi from Mortera, the Via Crucis from Sant’Ambrogio (about an hour’s walk), from the hamlet of San Pietro (about 15 minutes on foot), or by parking near the Sacra.

There is also a via ferrata starting at Croce della Bell’Alda, near the parking lot just outside Sant’Ambrogio, which climbs directly up to the walls of the Sacra di San Michele.I would never dream of attempting it myself, but apparently it is wonderful and suitable even for beginners (4 hours of climbing, 600 meters of elevation gain —don’t say I didn’t warn you). Here a small video of a couple that actually did it! I just get nervous watching it.

Before reaching the Sacra, you encounter the Sepulcher of the Monks: the remains of a Romanesque apse, probably a cemetery chapel, or perhaps—given its octagonal shape—a replica of the Holy Sepulcher, a symbolic reference for pilgrims visiting Jerusalem. Continuing on, the main complex comes into view, looking almost like a fortress thanks to its strategic position.

We are about forty kilometers from Turin, at the entrance to the Susa Valley along the Via Francigena, which made this site a crucial hub not only for pilgrims heading to Rome or Santiago de Compostela but also for merchants, nobles, clergymen, and armies.

The abbey was built between 983 and 987 at the summit of Mount Pirchiriano by a nobleman, Ugo di Montboissier. In its first century, thanks to the donations of wealthy pilgrims and the interventions of the papal curia, the Benedictine abbey increased enormously in power and wealth.

By the 11th century, San Michele had become a cultural and spiritual legend. Its library and grammar school had a European reputation. Nobles passing through often stayed, leaving generous offerings, land, and buildings. By the early 1200s, San Michele was at the height of its splendor and allied itself with the expanding House of Savoy.

Centuries of decline followed until 1836, when Carlo Alberto di Savoia attempted to revive the monastery by entrusting it to the Rosminian Fathers, who still manage it today.

The first thing that strikes visitors is the massive entrance, 41 meters in height. On the abbey’s website, the work of the Benedictine monks is described as “cyclopean”—with good reason.

Passing through the entrance, one finds the base of an imposing staircase that rises steeply (243 steps!) to the church above, built around the mid-12th century. Known as the “Stairway of the Dead,” it was used for the burial of abbots and supporters of the monastery. To enhance the solemnity of the climb, skeletons of monks were kept in a central niche until 1936.

A short way up, to the left, stands a pillar over 18 meters high that supports the church floor above.

Climbing these steps is considered a symbolic journey that unites physical and spiritual experience—you realize this about halfway up.

At the top stands the Zodiac Portal, a treasure of Romanesque art. Take a breath and observe the capitals and carvings carefully—it is worth it. The doorposts are decorated with zodiac signs on the right and constellations on the left. It is the oldest surviving Romanesque zodiac cycle.

Outside, you see four massive buttresses and flying arches added in the 1930s to support the southern wall of the church, which was showing dangerous signs of collapse. An additional ramp leads through a Romanesque portal into the church itself.

Begun around the mid-12th century to enlarge the primitive church built by Ugo di Montboissier, it fell into disrepair due to frequent raids over the centuries by Piedmontese, French, and Spanish soldiers and has undergone numerous restorations.

The apse is aligned with the exact point where the sun rises on the feast day of Saint Michael (September 29th).

Inside, at the end of the right nave, is a large 16th-century fresco depicting three distinct scenes: the burial of Jesus, the death of the Virgin Mary (rare in Catholic iconography), and the Assumption of Mary.

From the central nave, near the right pillar, you descend twelve ancient steps to the primitive sanctuary of Saint Michael. Scholars agree this was the first Sacra and the original center of devotion to Saint Michael.

Exiting the church, on the northwest side are the ruins of the “new monastery,” which once rose five stories high and housed monks during the abbey’s peak between the 12th and 14th centuries. Sadly, it collapsed centuries ago, and today only the evocative remains are visible. At the end of the wall of the ruins stands the Bell’Alda Tower, tied to a legend.

Alda, a young woman who had come to the Sacra to pray for protection from the evils of war, was attacked by enemy soldiers. To escape, she threw herself into the ravine, calling on Saint Michael and the Virgin Mary for help. Miraculously, she survived. But later, out of vanity and greed, she attempted to repeat the miracle for money, and this time no divine protector appeared. Alda was dashed to her death at the bottom of the cliff.

Was there ever a story where a woman wasn’t punished?

If you find yourself near Turin, along with the other things we have already recommended in past articles, don’t miss the chance to dedicate an afternoon to this extraordinary example of monastic life, where the Church expressed its deepest contradictions: building an almost inaccessible place clinging to rock, yet at the heart of a heavily traveled route for wealthy and powerful pilgrims.

Betti

How to get there:

Practical information:

Sacra di San Michele web site link here

Entrance requires a ticket (€8 for adults, €6 for children and teens 6–18). Pets are not allowed, and strollers cannot make the climb. Dedicated ramps and elevators are available for the disabled. On weekends, reservations are mandatory and can be made online on the official website, where you’ll also find updated hours and information.