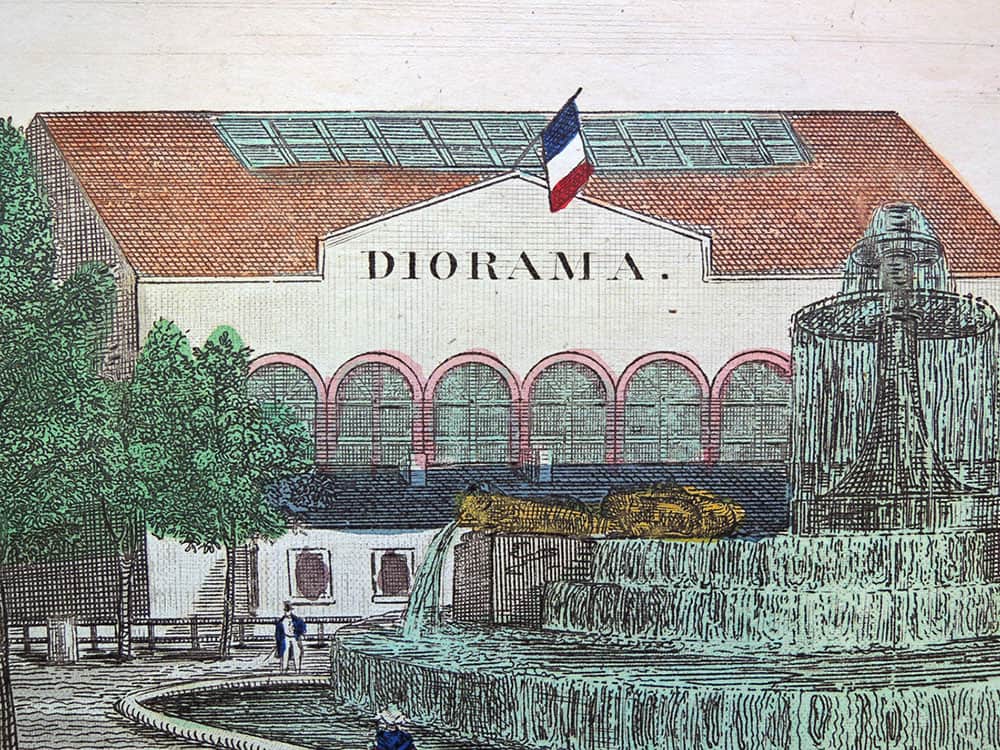

Presented to the public almost 200 years ago, the diorama can be considered the first immersive and virtual human experience. Its inventor, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787–1851), coined the term diorama, which comes from the Greek dià meaning “through” and òrama meaning “view.” The word therefore means “to see through” or “to see inside” something. (Mr. Daguerre is also credited with the term “daguerreotype,” one of the earliest known photographic processes in the world.)

A French artist and physicist, Daguerre created the first examples of dioramas between 1822 and 1827, with the aim of recreating stage sets so accurate they appeared real. With the invention of the diorama, we can mark the birth of sophisticated environmental illusion: over time, dioramas became tools for reproducing scenarios, events, historical figures, and animals—often life-sized—on display in museums, theaters, or places of worship.

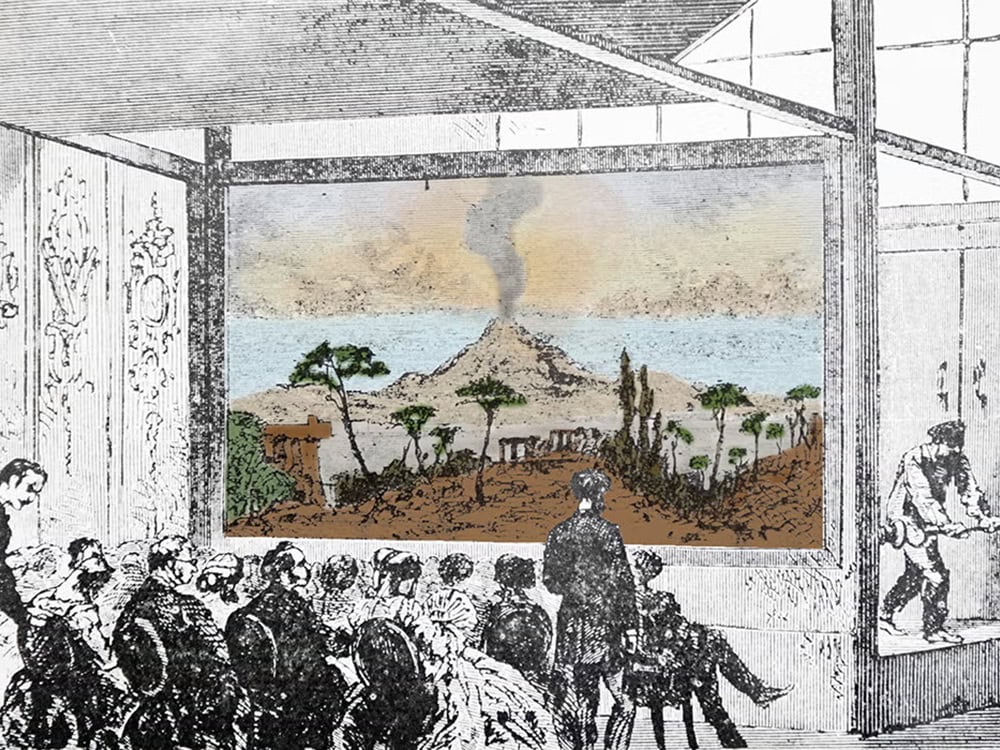

But back to our Mr. Daguerre: on February 20, 1826, in a small theater on the outskirts of London, a small group of spectators, immersed in complete darkness, watched in awe as the sun rose over Rosslyn Chapel (which later gained fame in 2006 thanks to the movie The Da Vinci Code), a magnificent 15th-century church located not in London, but in the Scottish countryside.

The first morning light revealed the majestic building, dimming slightly as a cloud passed overhead while bagpipes played faintly in the distance.

What made the diorama so captivating was witnessing the movement of an image, of a setting no longer static but capable of changing thanks to an ingenious play of light and projection.

Simultaneously, behind the screen, technicians used lighting tricks to create the illusion of passing time.

The diorama was long considered a direct precursor to cinema, but it could also be linked to virtual reality because of its immersive nature, capable of making viewers feel fully involved in the scene they were witnessing. The imagery was so evocative that directors, playwrights, and composers soon began incorporating the technology into their productions, eliminating the old-fashioned, heavily painted backdrops.

Today we live in a world where moving figures and environments are part of our visual routine. But in the early 1800s, the exotic imagination was fed exclusively by images from travelers and artists—rigid, two-dimensional figures. When viewers stepped into the neutral space of a diorama, they could forget their own reality and be physically transported to a world that, until that moment, was only imaginable.

This long introduction is meant to lead you to a place in the center of Milan that I’ve always loved. If you have the opportunity to spend a few days in our city, you’ll be able to experience the wonder of the diorama—and much more.

The Natural History Museum (Museo civico di storia naturale), located in the Giardini di Porta Venezia at Corso Venezia 55, holds Italy’s largest collection of dioramas—very realistic reconstructions of ecosystems that illustrate the planet’s biological diversity. Each diorama presents a real-life scene captured in the moment it occurs: the result is total visual immersion, and the stillness enhances the ability to observe the exquisitely detailed work made possible by the high-level artistic skill of the professionals involved.

Across its 5,000 square meters and 23 rooms spread over two floors, the Natural History Museum includes sections on mineralogy, paleontology, human evolution, entomology, malacology, and zoology. But it’s on the upper floor that you’ll find 83 dioramas created between 1965 and 2017. Following the museum route, you’ll travel from the mangrove forests of Borneo to Aldabra Island, to the underwater prairies of the Dahlak Archipelago, and the coral reefs of the Maldives.

A small aesthetic note: as you climb the grand staircase leading to the diorama floor, look up and don’t miss the ceiling decorated with high-relief carvings of large, stylized birds in flight—I’d love to have it in my bedroom!

If, during your trip to Italy, you sense that your school-age children are beginning to plot patricide after being dragged through yet another Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, or Rococo church, we suggest a visit to this museum as a refreshing break from your relentless art binge.

Hand in hand with your children, you’ll pass through African forests inhabited by forest buffalo, lowland gorillas, and okapis (the elegant Congolese giraffe-relative), then find yourselves in Asia or New Guinea, face-to-face with a banteng (an Asian bovine) or an orangutan. Alongside the beloved stars—monkeys, buffalo, lions, and giraffes—you’ll encounter a multitude of other animals, from small mammals to snakes, from birds to frogs, along with a vast array of insects, trees, herbs, flowers, and fruits, all painstakingly recreated to reflect their natural habitats in detail.

The environments depicted in the museum’s dioramas are drawn from national parks or protected nature reserves—often established to safeguard the very species on display, some of which are already endangered.

When our daughter Zoe was little, admission was free, and we often spent a few hours among dinosaur skeletons and insect displays on rainy days. Although an old-school museum might seem unappealing to today’s digital-age children, we can assure you its charm is undiminished: just recently, the children of some German friends who visited us were absolutely captivated and ran joyfully from one room to the next for a solid two hours.

Founded in 1838 during a time of great scientific advancement, the museum is Milan’s oldest civic museum, and the oldest natural history museum in Italy, attracting more than 300,000 visitors each year.

Its eclectic neo-Gothic architecture was, as in many European and North American cities, chosen to emphasize the historic nature of the institution—giving the new construction a scholarly, academic air. The abundant terracotta decorative elements on the facade recall the Lombard architectural tradition of using terracotta instead of stone (which was scarce in the region), as seen in civic and religious buildings from the late Gothic to the early Renaissance, when Donato Bramante and Leonardo da Vinci were in Milan at the court of Ludovico il Moro.

On the night between August 12 and 13, 1943, the museum was severely damaged by a British air raid on Milan. It was destroyed by fire and reopened only in 1952, thanks to a significant donation from Milanese doctor Vittorio Ronchetti, which made reconstruction possible.

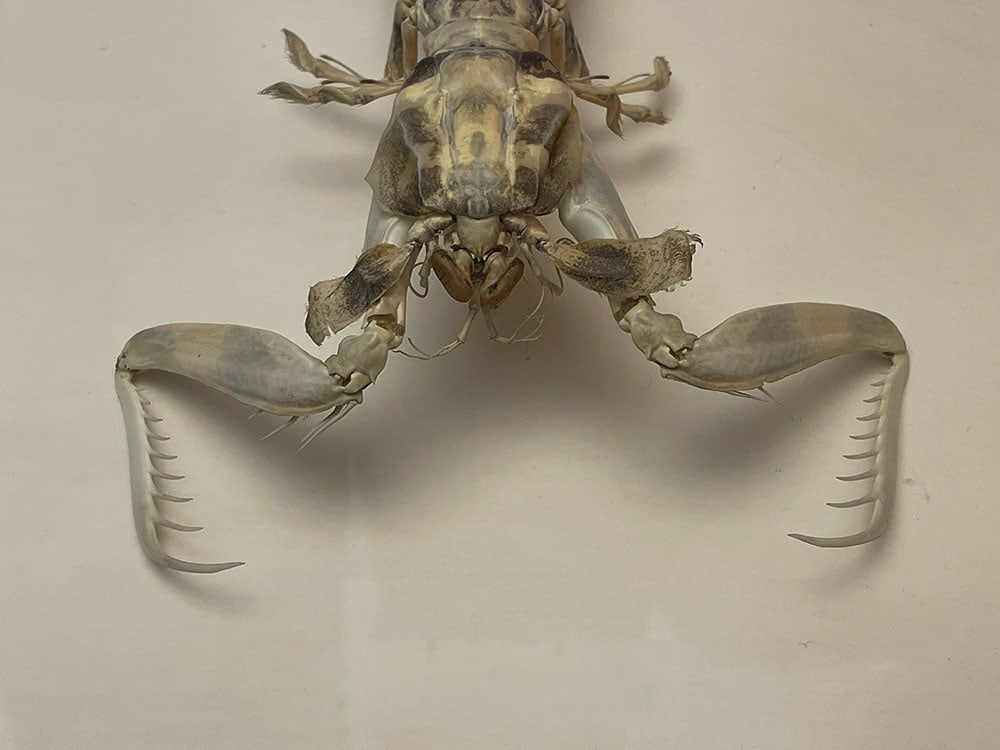

As I mentioned, the museum houses many dioramas that required precise scientific, technical, and artistic skills to create. Although each environment was designed by a team of researchers, the professionals who build the specimens and recreate the natural settings must have scientific knowledge to ensure the accuracy of the illustrated scene.

Creating a diorama takes six months to a year, depending on factors such as the availability of the animal to be included. Often these are very old or damaged specimens, requiring extensive restoration before display. Most of the animals at the Milan museum are real: it is one of the few museums in Italy with an in-house taxidermist who oversees the entire process—from skinning to tanning the hide for preservation.

(Taxidermy, from the Ancient Greek táxis = preparation and dérma = skin, is the technique of preserving an animal’s skin—especially vertebrates—by mounting it on a model that reproduces both the form and a natural posture. The work is completed with artificial parts like glass eyes or silicone tongues. When endangered or rare animals are depicted, perfectly realistic replicas are created instead.)

As for the setting, one of the main challenges in building a diorama is geometric—designing curved backdrops that create the optical illusion of a 3D space. The lighting must be meticulously planned to avoid unnatural shadows or lighting inconsistent with the represented environment.

Plant parts often use dried and recolored leaves and herbs, while heavier elements like trunks or rocks are made from lightweight materials like polyurethane or resin to avoid straining the flooring beneath. Since diorama environments are airtight, the displays remain well-preserved for long periods, though the animal skins are periodically treated with insecticides to prevent pest infestations.

Wax museums, anatomical collections, natural science exhibits, realistic depictions of Christ’s life in the chapels of the Sacri Monti, weeping statues carried in processions but kept in shadowed chapels most of the year. Our gaze slips into these “wunderkammer” of reproduced reality, similar to the original but giving us the privilege of observation and reflection, frozen in a suspended moment—a timeless instant that neither escapes nor ages.

The diorama freezes existence. It brings us face-to-face with a predator without danger—it’s suspended mid-leap, we witness its threat from behind a thick pane of glass, safe. And without the guilty feeling of having condemned a wild animal to life in prison for the sake of our curiosity.

I watched the children during our last visit.

The striped hides, the old tusks, the beaks, fins, claws, and webbed feet all worked their usual magic: once again, the dioramas invited us to look inside, captivating the eyes of the little humans who felt fear, tenderness, disgust, and affection toward those beautiful, deceiving puppets—fooled by nature cleverly portrayed, just as Mr. Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre had hoped 200 years ago.

Go visit!

Betti

Web Site link for ticket purchase and openning hours: https://museodistorianaturalemilano.it/

How to get there when you are in Milan: